Spiking Neural Networks on Neuromorphic Processors

For the first part of our exercise, we will dive into the remarkable world of biological neurons. Neurons are cells consisting of mostly water, ions, amino acids and proteins with unique electrochemical properties. They are the primary functional units of the brain. Our thoughts, perceptions and memories are the results of molecular movement across neural membrane and the synaptic transmissions between these neurons. Understanding neurons and neural computation can help illuminate how our rich mental experiences are constructed and represented, the underlying principles of our behavior and decision making, as well as provide biological inspiration for new ways to process information for artificial intelligence.

This page will be an interactive overview of biological neurons, by no means intended to be comprehensive

Before we dive into mathematical model of an ideal spiking neuron, we should first take a brief tour of the biology of a neuron, it all its glory (you might be familiar with this part if you've taken other Neuroscience courses).

The first thing to appreciate about neurons is their specialized morphology, i.e. their form and structure. It allows them to receive information from more than $10^4$ mostly neighbouring cell bodies and communicate rapidly over long distances, sometimes from the spinal cord to the feet (up to a meter!). In the mammalian cortex

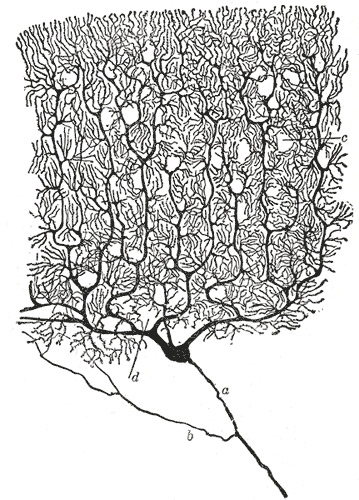

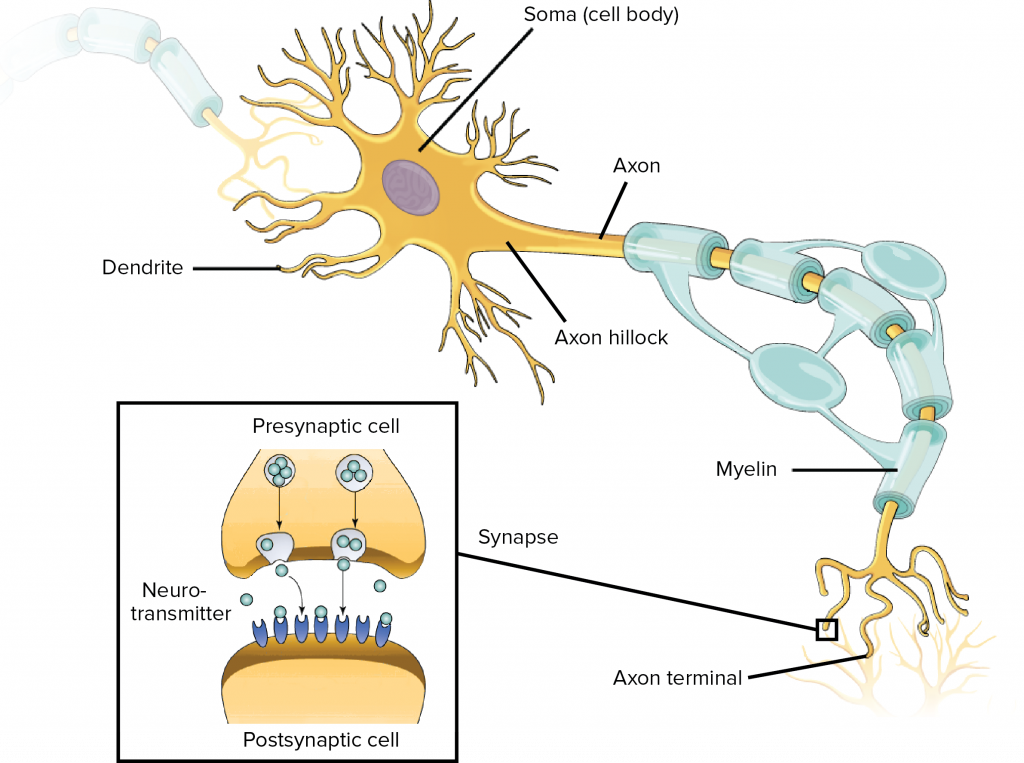

Neurons receive signals from other neurons through synapses located – not exclusively – on their dendritic tree, which is a complex, branching, sprawling structure. If you are wondering what the king of dendritic complexity is, that would be the Purkinje cell, which may receive up to $10^5$ other connections. Dendrites are studded with dendritic spines – little bumps where other neurons make contact with the dendrite. Signals from the dendrites propagate to and converge at the soma – the cell’s body where nucleus and other typical cell organells live.

Coming off the soma is the axon hillock which turns into the axon. The axon meets other neurons at synapses. It allows a neuron to communicate rapidly over long distances without losing signal integrity. To allow signals to travel rapidly, the axon is myelinated – it is covered with interspersed insulators which allows the neuron’s signal to jump between insulated sections. To allow the signal to maintain integrity, the neuron signal in the axon is ‘all-or-nothing’ – it is a rather bit-like impulse, which we will discuss next.

The second thing to appreciate about neurons is their specialized physiology — that is the cellular functions of neurons. The most striking feature of neural cellular function is the action potential, or "spikes". This is the mechanism which allows neurons to transmit information reliably over long distances without the transmission attenuating.

It is important to remember that neurons live in an extracellular solution of mostly water, salts and proteins. The forces caused by the movement of salts into and out of the cell and the different concentrations of these salts is the physical basis of the neuron’s remarkable behavior. There are sodium-potassium pumps which move sodium out of the cell and potassium in, so that the concentration of sodium outside the cell is higher than inside and the concentration of potassium outside the cell is lower then inside.

An action potential is a discrete event in which the membrane potential rapidly rises (depolarization) and then falls (polarization). This discrete event is all-or-nothing, meaning that if an action potential occurs at one part of the neurons membrane, it will also occur in the neighboring part, and so on until it reaches the axon terminal. Action potentials typically have an amplitude about 100 mV and duration of 1-2 ms

The action potential is the result of different types of ions traveling across the cell membrane through channels and the activation and inactivation of those channels on different time scales. A classic action potential occurs as follows:

As we will see below, there exist different neuron models that capture the essence of an action potential mechanism with varying details. But, the general working principle still holds: neuron takes spike inputs from other neurons with its dendrites, performs a non-linear processing at soma - if the total arriving input is higher than a certain threshold it generates an action potential. The action potential is then transferred to other neurons using its axons.

Spikes are the language of neurons and we usually deal with a series of spikes. We can formally define them with:

\[\rho(t)=\sum_{i=1}^{k} \delta\left(t-t_{i}\right)\]where an impulse is described with a dirac delta function (which is convenient for representing discrete events):

\[\delta(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}1 & \text { if } \mathrm{t}=0 \\ 0 & \text { otherwise }\end{array}\right.\]Often, it is useful for analysis to assume spike trains are generated by a random processes due to existence of various noise factors. Assuming spikes are independent of each other, we can model the generation of the spikes as a Poisson process, in which we know the probability $n$ spikes occur in the interval $\Delta t$ :

\[P\{n \text{ spikes occur in } \Delta t\}=\frac{(r t)^{n}}{n !} \exp (-r t)\]In practice, to generate spikes according to a Poisson point process, we generate a random number $r$ in a sufficiently small time interval e.g., 1 ms, such that only 1 spike should occur, and check whether $r$ is smaller than the firing rate $\Delta t$. However, we make sure that firing rate $\Delta t<1$. We are going to implement this process in the next exercise.

If you weren’t constrained to thinking about ion channels — that is, if, for a moment, you could allow yourself to look past the wetware, the biological hardware — could you capture aspects of cell behavior relevant to neural computation while maintaining the simplicity needed for tractable analysis and simulation. The intuition behind Eugene Izhikevich’s simple model

Here, $u$ and $v$ are dimensionless variables, $a,b,c,d$ are dimensionless parameters, $t$ is time. The variable $v$ represents the membrane potential of the neuron and $u$ represents the membrane recovery variable which accounts for the activation of $K^{+}$ ionic currents and inactivate $Na^+$, basically provides the leaking effect. $I$ is the synaptic currents injected to soma.

Now it's time to play! You can adjust the model parameters below to simulate some known neuronal dynamics. We suggest you to check Izhikevich's Simple Model of Spiking Neurons paper to find proper model parameters for achieving regular spiking, intrinsically bursting, chattering, fast spiking etc.

Neurons decode information from other neurons, transform this information, and then encode information to other neurons in the form of spikes. The computational properties of neurons enable them to perform this operation. Below are some examples of computational properties (the list is by no means comprehensive).

One way to look at the computational powers of neurons is to look at their F-I functions — that is, their gain functions. Hodgkin proposed 3 classes of neurons

It should be said that there are many other ‘types’ of neurons. That is, there is more to neurons than their gain functions. In fact there is a project at the Allen Institute working on the lumping of neurons into types. They have an amazing open source brain cell database.

We can also consider whether neurons are either integrators or resonators. Integrators accumulate signals until their membrane potential reaches a well defined threshold. Closely timed signals are added together and have greater affect than when far apart. Integrators are coincidence detectors. Some integrators are Type 1 neurons.

Resonators resonate (oscillate) in response to incoming signals. Resonators do not necessarily have clearly defined thresholds. The threshold is fuzzy. Unlike integrators, resonators are most sensitive to a narrow band of frequencies. Resonators are coincidence detectors as well, but they are also frequency detectors. All resonators are type 2 neurons.

The credit of most of the content of this post goes to Jack Terwilliger. For more detailed interactive models of biological neurons we highly encourage you to check his amazing blog. We are currently working on updating the scope of this post.